In Bengal, winter doesn’t arrive with dates on a calendar. It arrives with a smell.

A faint, smoky sweetness in the air. Milk simmering slowly. The quiet excitement in homes when someone says, “Ebarer gur ta khub bhalo hoyeche.” (“This year’s jaggery is really good.”)

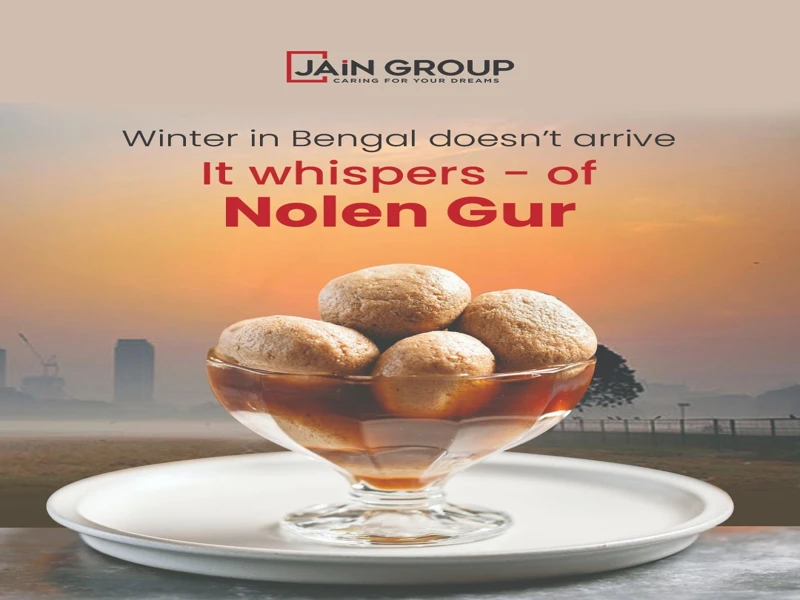

That smell is Nolen Gur — the soul of Bengali winter.

Long before sugar became common, Bengal sweetened its life with date palm jaggery. Known as Gur or Nolen Gur, it is extracted from the sap of date palm trees during the coldest months — usually from November to February.

The process is delicate and seasonal. At dawn, palm tappers climb tall trees to collect sap that flows only in winter’s chill. By midday, the sap is boiled carefully over wood fires until it thickens into a golden, aromatic jaggery.

This tradition dates back centuries — when Bengal was an agrarian land, dependent on nature’s rhythm. Winter wasn’t just about harvest; it was about gratitude, celebration, and sweetness earned through patience.

Before Partition, Bengal was one land, one culture, one taste.

From Kolkata to Khulna, Burdwan to Barisal, Nolen Gur flowed freely into kitchens across undivided Bengal. The recipes, techniques, and love for date palm jaggery were shared across what is now West and East Bengal.

Despite borders, the taste remains unchanged — a reminder of shared roots, shared winters, and shared memories.

For many families divided by history, Nolen Gur is one of the few traditions that remains whole.

Soft, fragrant, understated. The gentle sweetness of jaggery blends with fresh chhana to create a dessert that feels like comfort itself.

A winter favourite that melts differently — deeper, richer, warmer than its sugar-syrup counterpart.

Slow-cooked with gobindobhog rice, milk, and jaggery, this payesh is winter in a bowl. Served warm, it carries blessings, memories, and nostalgia.

Rice flour, coconut, jaggery — simple ingredients, infinite emotion. From Patishapta to Bhapa Pithe, winter pithe owes its soul to Nolen Gur.

Each part of West Bengal gives Nolen Gur its own expression:

Though recipes vary, the emotion remains the same — winter is sweeter with Nolen Gur.

What was once a seasonal household treasure has now crossed oceans.

Today:

Yet no matter how global it becomes, Nolen Gur never loses its intimacy. It still tastes best when eaten slowly, during cold evenings, wrapped in memories.

Perhaps it’s because it is temporary. It comes, stays briefly, and disappears. Or because it reminds us that good things require time — time to grow, collect, cook, and cherish.

In a world of instant sweetness, Nolen Gur teaches patience.

It tells us that winter is not just about cold — it’s about warmth created within.

Soon, the palm trees will stop flowing. The gur vessels will empty. The sweets will change.

But for Bengalis, winter will always be remembered by its taste.

A spoon of payesh. A bite of sandesh. The aroma of jaggery melting into milk.

Nolen Gur is not just a sweetener. It is history. It is home. It is winter — preserved in sweetness.

No matter where a Bengali lives, when winter arrives, so does the longing.

For Nolen Gur.